I only realised I was asexual when everyone else seemed to realise that they weren’t.

We were approaching the end of primary school, and after coming back from the summer holidays, I noticed that my peers were less interested in playing together and more interested in ‘fancying’ each other. It seemed to come out of nowhere, and while I rolled my eyes as girls argued over boys in the cafeteria, I assumed I’d be doing the same thing soon enough. Whether it was the beginnings of sexual attraction, or the arrival of romantic attraction was difficult to determine, but I knew those feelings were on the horizon. It would only be natural. So why didn’t it happen?

Recognising I was different at school

Over time, my eleven-year-old self started to wonder if I had reacted too strongly to the pre-teen dramas I witnessed and somehow broken the process. I envisioned a car going along a bridge that severed in the middle, either causing the car to plummet into the depths below or remain where it was, while everyone else’s car made it to the other side. Had I severed the bridge? There was no way to know. It wasn’t like asexuality ever came up in our sex education classes. At the same time, the thought of trying to ‘fix the problem’ and be more like everyone else didn’t entirely appeal to me either. It was why I decided to go to an all-girls secondary school.

I was under the naïve belief that if there were no boys, then girls wouldn’t care about those kinds of relationships anymore, and no one would notice that I was different. Of course, that idea completely backfired when it became clear that most of the girls felt deprived of boys, and thus my complete disinterest was even more obvious.

It wasn’t long before it became a running gag to work out what was “wrong” with me. There had to be some explanation for why I was so abnormal. My peers came up with a range of assumptions. Like that I must have a hormonal condition, or maybe I was a psychopath who couldn’t connect with anyone and thus wasn’t attracted to anyone. Or maybe I was traumatised because of childhood trauma I couldn’t remember. Or maybe I was a lesbian who hadn’t worked it out yet.

Being black and asexual and labelled as ‘slow’

However, the assumption that stuck the most was that I was just “slow.” I was regarded as being in an infantilised state because I didn’t hit the milestones that were seen as a sign of physical and psychological maturity for teenagers – all of which were based on sexual and romantic behaviours.

It’s an expectation that’s placed on Black girls even more, as we’re on the receiving end of both sexualisation and 'adultification' from a younger age. The intersections I existed in made it impossible for anyone to believe that I was asexual and that there wasn’t a more unpleasant explanation for my lack of sexual attraction towards others. It also made those stereotypes more dangerous, because if there’s one thing you don’t want to be labelled as a Black kid in public education, it’s “slow.”

Intersectional inequalities and black prejudice

The UK has a long history of treating Black students unequally. It can be found back in the 70s, when Black students were disproportionately put into schools for the “educationally subnormal.” Even today, a recent Guardian Report found that ‘exclusion rates for Black Caribbean students in English schools are up to six times higher than those of their white peers in some local authorities.’ Our natural hair can even be one of the reasons for our punishment. I was a prefect in secondary school, but I was still almost excluded for having a red streak in my braids. Meanwhile, my white friends could dye their straight hair whatever colours they wanted.

Being treated differently by teachers was not new to me. In primary school, I was put into an extra class for ESL children, even though English is my native language and I was getting high marks in the subject. However, it was in secondary school where I experienced teachers being influenced by – and participating in – my bullying.

They picked up on the whisperings of the students and would single me out for being ‘less intelligent’ than my classmates, despite there being no evidence to suggest this. One of my teachers even nicknamed me “Sp*zmin.” Others told me that they wouldn’t select me for extra tutoring because they knew I wouldn’t get a C anyway. At the end-of-year event, my teachers joined the students to vote me as, “Most likely to still be living at home” when I’m thirty, in front of the entire year group. Everyone laughed. I didn’t.

Healing from trauma at school to become a multi-award-winning Ace activist

To an extent, maybe they can’t be blamed for branding me with such a harsh misconception. After all, the teachers knew less about asexuality than the students did, and in a system that hadn’t yet come to terms with its racism, it was easy to believe that there was just something “wrong” with the Black girl who was different. I have had to spend years healing from my traumatic experiences in school. It made me determined to prove everyone wrong, even to the extent of becoming an extreme perfectionist, as I didn’t want to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

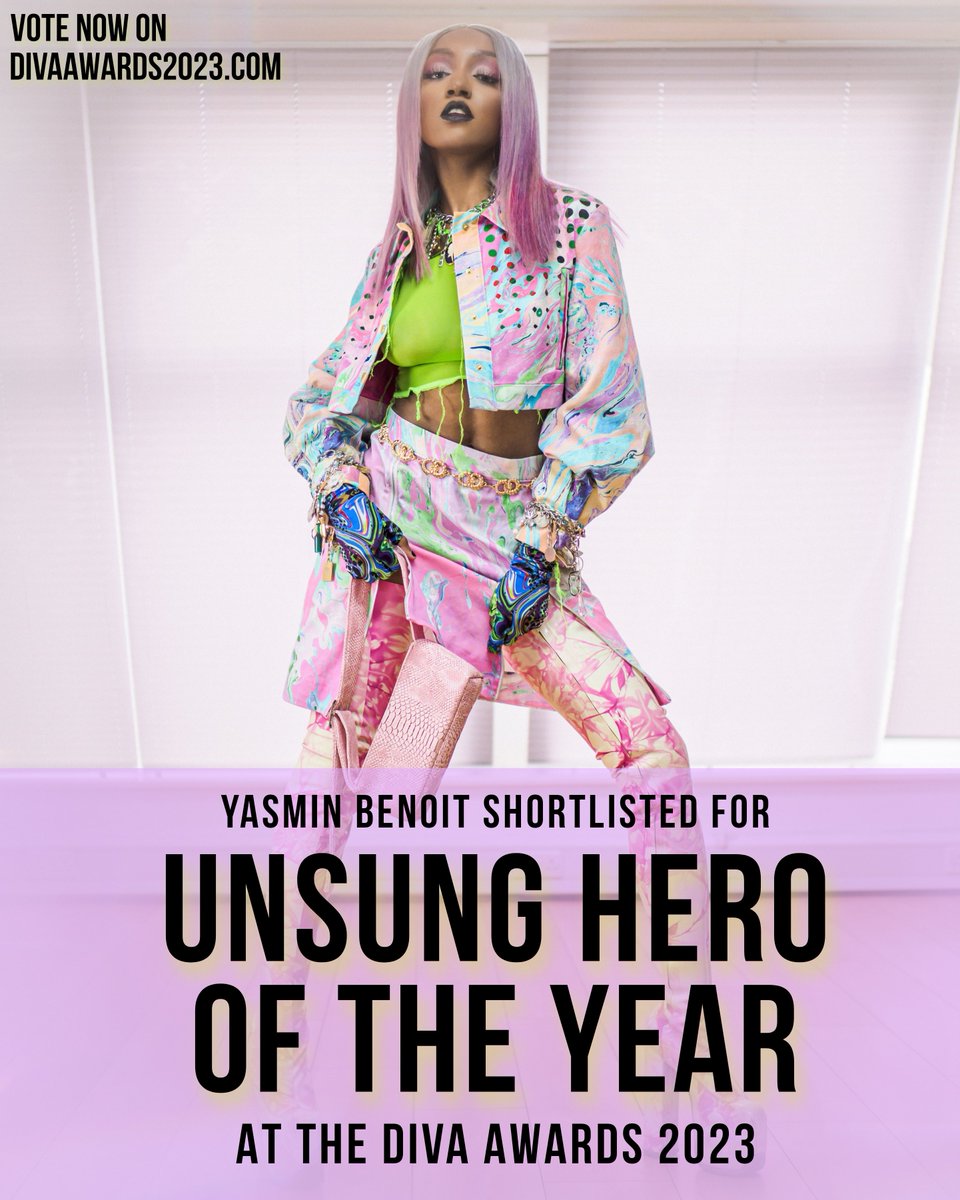

I went on to get a scholarship to attend a private school for sixth form. After that, I attended St. Mary’s University in Twickenham and graduated with a First-Class BSc Sociology degree in 2017. I earned an MSc Crime Science degree from UCL (with Merit) in 2018.Now, I’m a multi-award-winning activist, model, writer, speaker, researcher and consultant, something I achieved through perseverance and staying true to myself.

The importance of education in combatting prejudice

As an adult, I can’t help but think of how so many of my negative experiences could have been avoided – ironically – with education. Not just education about asexuality, but asexuality and race – an acknowledgement of how someone’s intersections can make a big difference. I continue to work towards a future where asexuality is recognised and accepted in education, healthcare, at work, and in wider society.